Virtuality

| Virtuality | |

|---|---|

| |

| Information | |

| Type | Public Company (1993-1997) |

| Industry | Virtual Reality, Electronics, Interactive Entertainment, Arcade Games, Video game hardware |

| Founded | October 1987 (as W Industries), renamed to Virtuality Group in 1993 |

| Founder | Dr. Jonathan D. Waldern |

| Headquarters | Leicester, England, United Kingdom |

| Notable Personnel | Dr. Jonathan D. Waldern (Founder, CEO, CTO), Al Humrich, Richard Holmes, Terry Rowley, Dennis Ohryn, Ray Ticer, Don McIntyre |

| Products | Virtuality 1000 Series, Virtuality 2000 Series, Virtuality 3000 Series, Project Elysium, Space Glove, Visette, Mega Visor Display, VR-1 (with Sega), Atari Jaguar VR prototype |

| Website | virtuality.com |

- See also: Companies

Virtuality Group plc (originally founded as W Industries) was a pioneering virtual reality company based in Leicester, England, that developed and commercially produced some of the world's first VR arcade machines and entertainment systems in the early 1990s. Founded by Dr. Jonathan D. Waldern in 1987, Virtuality became one of the most influential companies in the first wave of virtual reality technology, creating immersive gaming platforms and innovative VR hardware solutions for both entertainment and professional applications.

History

Origins and founding (1985-1989)

Virtuality's roots can be traced to the academic research of Dr. Jonathan D. Waldern at the Human Computer Interface Research Unit of Leicester Polytechnic (now De Montfort University) in the early 1980s.[1] By 1986, Waldern had developed a system known as the "Roaming Caterpillar" that could deliver a stereoscopic view of a three-dimensional scene using a moveable CRT screen with shutter glasses and acoustic sensors for tracking head and hand movements.[2]

In October 1987, Waldern established W Industries (named after himself) along with software specialist Al Humrich, mathematician Terry Rowley, and engineer Richard Holmes, with the goal of commercializing 3D visualization technology.[3] The four founding members pooled their individual expertise and resources, with Rowley, Holmes, and Humrich each contributing £2,500, while Waldern invested considerably more and maintained a majority stake in the company.[4]

Initial funding was difficult to obtain as companies were wary of the expensive technology.[5] However, in 1989, their fifth prototype became the basis for the first commercial Virtuality system and won the British Technology Group Award for Best Emerging Technology,[6] securing a £20,000 prize and £1 million in investment from a leisure firm.[7]

Commercial breakthrough and expansion (1990-1994)

Virtuality achieved its commercial breakthrough in November 1990 when it launched the Virtuality 1000SU VR system at the Computer Graphics '90 exhibition held at Alexandra Palace in London.[8] This system, despite its crude graphics by today's standards, was described by Computer Gaming World in 1992 as offering "all the necessary hallmarks of a fully immersive system at what, to many, is a cheap price".[9]

The company's initial focus was on professional and industrial applications. The first two networked VR systems were sold to British Telecom Research Laboratories for networked telepresence experiments, with other early systems sold to corporations including Ford, IBM, Mitsubishi, and Olin.[10]

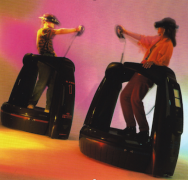

In 1991, capitalizing on growing public interest in virtual reality, the company released an arcade version of the 1000SU called the 1000CS (CS referring to "cyberspace"), which brought VR gaming to the public.[11] This coincided with increasing media attention on virtual reality technology, exemplified by the 1992 science fiction film "The Lawnmower Man," which helped popularize the concept of VR.

In 1991, Leading Leisure Plc invested £600,000 for a 75% stake in the company, providing crucial early capital.[12] For the year ending December 31, 1992, Virtuality reported a 200% increase in turnover to £5.3m and its first pre-tax profit of £214,000.[13]

Public flotation and partnerships (1993-1995)

In 1993, W Industries officially changed its name to Virtuality Group plc to align with its product branding and prepared for a public stock offering. In November 1993, Virtuality successfully went public on the London Stock Exchange, with shares starting at 170p and reaching 315p on the first day, valuing the company at £75m. Waldern, retaining a 10.4% stake, was worth over £7m, and the flotation brought in £12.6m, with Waldern selling part of his holding for £750,000.[14]

In January 1995, the company expanded its executive team, bringing in Dennis Ohryn as Deputy Executive Chairman and Ray Ticer as Finance Director, together bringing over 50 years of experience from technology companies such as Prime Computers, Sun Microsystems, and Apple.[15]

During this period, Virtuality engaged in several high-profile collaborations:

- Sega VR-1 / Mega Visor Display – In June 1993, Virtuality signed a deal with Sega Enterprises Ltd, worth £2.3m for the first two years and £1.3m annually thereafter, to license its operating system for the Sega VR-1 theme park attraction at Joypolis in Yokohama, Japan. The attraction used Virtuality's Mega Visor Display with 756 × 244 pixel resolution per eye and was expected to sell 2,000 units yearly starting in 1994.[16] They also co-developed the arcade game Netmerc (or TecWar) for Sega's Model 1 hardware.[17]

- Atari Jaguar VR – In 1994, Atari Corporation commissioned Virtuality to develop a VR headset for the Atari Jaguar console. Two color-coded prototypes were shown in 1995, but the project was never commercially released due to issues between the companies and the eventual failure of the Jaguar platform. The sunk costs from this project contributed to Virtuality's financial difficulties.[18][19]

- IBM Project Elysium – In July 1994, Virtuality partnered with IBM to launch Project Elysium, a virtual reality system for use in architectural, medical, and educational markets. It was a complete integrated VR workstation based on IBM's ValuePoint PCs that included development software tools, the Visette 2 headset, and the V-Flexor hand-held controller.[20][21]

Decline and bankruptcy (1996-1997)

By the mid-1990s, Virtuality faced increasing challenges as the initial VR hype began to wane. The company struggled with the high cost of its systems (around $65,000 per unit), declining arcade popularity, and competition from home gaming consoles.[22] The rapid advancements in PC and home console technology (Commodore went bankrupt in 1994) began offering increasingly sophisticated graphics at lower prices, eroding the unique selling proposition of expensive arcade VR.[23]

Despite attempts to diversify into home VR systems, professional applications, and collaborations with companies like Atari for the Jaguar VR headset, Virtuality was unable to maintain its market position.[24]

On February 11, 1997, Virtuality Group entered bankruptcy amid the broader collapse of the first-wave VR industry, which also saw the demise of other pioneering VR companies like Forte Technologies and VPL Research within months of each other.[25] By this time, approximately 1,200 Virtuality arcade machines were in use worldwide.[26]

Post-bankruptcy (1997-present)

Following bankruptcy, the company's assets were divided. The rights to the entertainment machines (but not the Virtuality brand itself) were sold to Cybermind Interactive Europe in 1997.[27] These assets were later acquired by Arcadian Virtual Reality LLC in 2004, which operated until 2012, when it was acquired by VirtuosityTech, Inc., the current owner of the arcade machine assets.[28]

Dr. Jonathan Waldern continued his work in immersive technology after Virtuality's bankruptcy. In 1997, he founded Retinal Displays, which produced head-mounted displays that were licensed to Japanese toy manufacturer Takara as the "Dynovisor" and to Philips as the "Scuba Visor," selling over 160,000 units combined.[29][30]

Waldern later founded DigiLens Inc. in 2004, a company specializing in diffractive optical waveguide technology for augmented reality displays. In January 2017, DigiLens raised $22 million in capital to develop AR displays no thicker than regular eyeglass lenses, with applications in automotive, aerospace, and military industries.[31]

Today, the legacy of Virtuality is preserved by enthusiasts and museums, including the Retro Computer Museum in Leicester, which displays and maintains working Virtuality machines. VirtuosityTech has announced plans to port classic Virtuality games to modern VR platforms, allowing a new generation to experience these pioneering virtual reality titles.[32]

Products and technology

Arcade systems

Virtuality produced several generations of VR arcade systems:

1000 Series (1990-1994)

The original Virtuality systems came in two configurations:

- 1000SU (Stand-Up): Featured a waist-high ring with a magnetic source for tracking, where the player would stand and use a free-moving "Space Joystick" controller

- 1000SD (Sit-Down): Players would sit down with various control options including joysticks, a steering wheel, or aircraft yoke depending on the game[33]

The 1000CS (Cyberspace) variant, released in 1991, was specifically designed for arcades. It was priced at approximately $60,000 per unit, with around 350 units produced - 120 of which were installed in the United States.[34]

The 1000 series was powered by a Commodore Amiga 3000 with 4 MB of RAM and a CD-ROM drive. The system included a pair of graphics accelerators (one for each eye) based on Texas Instruments TMS34020 GSP (Graphics System Processor) chips with TMS34082 floating-point co-processors. Each of these cards could deliver about 40 Mflops with the capability to render 30,000 polygons per second at 20 frames per second.[35] The system provided <50 ms latency for networked multiplayer experiences.[36]

2000 Series (1994)

The 2000 Series (both SU and SD models) featured significant improvements:

- Intel 486-based PC as the host computer

- Expality PIX 1000 proprietary graphics card with dual Motorola 88110 RISC processors

- Enhanced visette headset with higher resolution (800x600 pixels per eye) delivered by two 1.6" LCD screens

- Improved lens system for a wider field of view

- Texture mapping and other enhanced graphics capabilities[37]

3000 Series

The 3000 Series was an upgrade to the 2000 Series that featured:

- Intel Pentium processor

- Rifle-shaped VR controller available in two versions:

* Standard SU-3000 with a generic rifle controller * "Total Recoil" version with a replica Winchester controller featuring a CO2-powered blowback mechanism[38]

Hardware components

Visette

The Visette was Virtuality's head-mounted display (HMD):

- The original Visette used in the 1000 series featured two Panasonic LCD screens with a resolution of 372x250 pixels per eye

- The Visette 2, used in the 2000 series, improved the resolution to 800x600 pixels per eye

- The headsets included integrated headphones for audio and a microphone for voice communication in multiplayer games

- The 1000 series Visette weighed approximately 3.5 kilograms, making it significantly heavier than modern VR headsets[39]

Tracking systems

Virtuality used magnetic tracking systems to monitor players' movements:

- The 1000 series used a Polhemus "Fast Track" magnetic tracking system

- The 2000 series employed a Polhemus InsideTrak magnetic tracking card that could position multiple objects at a range up to 76 cm from a transmitter in 6 degrees of freedom (6DoF) with a static accuracy of about 1.3 cm and 2 degrees of rotation[40]

Space Glove

In 1991, Virtuality released the "Space Glove," a VR data glove peripheral that could:

- Track the position of the user's hands

- Measure one angle of flex for each finger and two angles for the thumb using 12-bit A/D converters[41]

- A Force-Feedback variant was released in 1994[42]

Software and games

Virtuality developed numerous games and experiences for its systems, including:

- Dactyl Nightmare: The most iconic Virtuality game, a multiplayer first-person shooter featuring platforms where players competed in deathmatch or capture the flag modes. A pterodactyl would occasionally swoop down to pick up unwary players.[43]

- Dactyl Nightmare 2 - Race For The Eggs!: The sequel to the popular original game

- Grid Busters: A robot shoot-em-up

- Hero: A locked door puzzle game

- Legend Quest: A fantasy adventure

- Battlesphere: A space battle game

- Exorex (originally titled "Heavy Metal"): A multiplayer mecha robot battle game

- Total Destruction: A stock car racing game

- VTOL: A Harrier jump jet simulator

- Flying Aces: A biplane dogfight simulator

- Zone Hunter: Released for the 2000 series, co-developed with Taito[44]

- Pac-Man VR: A virtual reality adaptation of the classic arcade game

- Zero Hour: A first-person on-rails shooter designed for the rifle controller of the 3000 series

- Quickshot Carnival: A shooting gallery game featuring clay shooting and other target practices for the "Total Recoil" version[45]

- Boxing: A boxing simulation game[46]

- Netmerc / TecWar: Co-developed with Sega for their hardware[47]

Professional applications

Beyond entertainment, Virtuality developed several systems for professional use:

- Project Elysium: A virtual reality system developed in partnership with IBM for use in architectural, medical, and educational markets. It was a complete integrated VR workstation that included development software tools, the Visette 2 headset, and the V-Flexor hand-held controller.[48]

- Ford Galaxy VR Experience: A VR attraction created in partnership with Creative Agency Imagination for the launch of the 1995 Ford Galaxy

- LIFFE Virtual Trading Floor: A virtual trading floor developed for the London International Financial Futures and Options Exchange[49]

- Oil Rig Evacuation Simulator: A training system simulating the evacuation of an exploding oil rig

- Surgical Training Simulator: A system designed to test surgical skills in a virtual operating theater[50]

Legacy and influence

Virtuality is widely recognized as one of the most significant pioneers of commercial virtual reality technology. The company's arcade machines represented the first exposure to virtual reality for many people in the early 1990s, creating a foundation for public understanding and interest in VR that would later support the modern VR revival.

While the company ultimately failed as a business venture, Virtuality demonstrated the potential for immersive virtual experiences and multiplayer virtual environments. Many of the concepts introduced in Virtuality's systems, such as 6DoF tracking, motion controllers, and networked multiplayer VR, remain central to modern VR technology.

At its peak, the company operated over 1,200 arcade machines worldwide, primarily in the United States and Japan, significantly outperforming its nearest competitor, which sold only 25 units.[51] These systems demonstrated many core principles: head-tracked stereoscopy, networked multiplayer, and 6-DOF interaction that underpin modern VR arcades and consumer headsets.[52]

Today, the legacy of Virtuality is preserved by enthusiasts and museums, including the Retro Computer Museum in Leicester, which displays and maintains working Virtuality machines. VirtuosityTech, the current owner of the arcade machine assets, has announced plans to port classic Virtuality games to modern VR platforms, allowing a new generation to experience these pioneering virtual reality titles.[53]

Virtuality's contribution to the development of VR has been summed up by Simon Marston, a VR collector who restores Virtuality machines: "Virtuality was the world leader in VR at one point; without the company, we must question if VR would have made its reappearance again in more recent years."[54]

Images

References

- ↑ Virtual Reality Society, "Virtuality – A New Reality of Promise, Two Decades Too Soon", April 17, 2018. https://www.vrs.org.uk/dr-jonathan-walden-virtuality-new-reality-promise-two-decades-soon/

- ↑ Wikipedia, "Virtuality (product)", March 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtuality_(product)

- ↑ Time Extension, "The Making of Virtuality, The 1990s Pioneer That Sold The World On VR", December 7, 2023. https://www.timeextension.com/features/the-making-of-virtuality-the-1990s-pioneer-that-sold-the-world-on-vr

- ↑ Time Extension, "The Making of Virtuality, The 1990s Pioneer That Sold The World On VR", December 7, 2023. https://www.timeextension.com/features/the-making-of-virtuality-the-1990s-pioneer-that-sold-the-world-on-vr

- ↑ Virtual-Reality-Shop, "The History of VR – Part 14: The Beginning of the End, of the Beginning", December 7, 2021. https://www.virtual-reality-shop.co.uk/the-complete-history-of-vr-part-14/

- ↑ LinkedIn, "DigiLens founder departs…", August 5, 2020. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/digilens-founder-departs-christopher-grayson?trk=read_related_article-card_title

- ↑ Tech Monitor, "W Industries changes its name to Virtuality, plans float by Christmas", September 1, 1993. https://web.archive.org/web/20240311144735/https://techmonitor.ai/technology/w_industries_changes_its_name_to_virtuality_plans_float_by_christmas

- ↑ Wikipedia, "Virtuality (product)", March 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtuality_(product)

- ↑ Wikipedia, "Virtuality (product)", March 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtuality_(product)

- ↑ VirtuosityTech, "About Us". https://virtuositytech.com/index.php/about-us

- ↑ Wikipedia, "Virtuality (product)", March 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtuality_(product)

- ↑ The Independent, "Dr Waldern's Dream Machines", November 28, 1993. https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/the-hunter-davies-interview-dr-walderns-dream-machines-arcade-thrills-for-spotty-youths-today-but-revolutionary-tools-for-surgeons-and-architects-tomorrow-says-the-pioneer-of-virtual-reality-1506176.html

- ↑ Tech Monitor, "W Industries changes its name to Virtuality, plans float by Christmas", September 1, 1993. https://web.archive.org/web/20240311144735/https://techmonitor.ai/technology/w_industries_changes_its_name_to_virtuality_plans_float_by_christmas

- ↑ The Independent, "Dr Waldern's Dream Machines", November 28, 1993. https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/the-hunter-davies-interview-dr-walderns-dream-machines-arcade-thrills-for-spotty-youths-today-but-revolutionary-tools-for-surgeons-and-architects-tomorrow-says-the-pioneer-of-virtual-reality-1506176.html

- ↑ Virtual-Reality-Shop, "The History of VR – Part 14: The Beginning of the End, of the Beginning", December 7, 2021. https://www.virtual-reality-shop.co.uk/the-complete-history-of-vr-part-14/

- ↑ Sega Retro, "Mega Visor Display". https://segaretro.org/Mega_Visor_Display

- ↑ Wikipedia, "Virtuality (product)", March 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtuality_(product)

- ↑ Wikipedia, "Virtuality (product)", March 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtuality_(product)

- ↑ JagCube, "Jaguar VR Information!". https://jagcube.atari.org/jaguarvr.html

- ↑ Virtuality.com. https://virtuality.com/

- ↑ Tech Monitor, "IBM Launches Virtuality System As Project Elysium VR", July 27, 1994. https://www.techmonitor.ai/technology/ibm_launches_virtuality_system_as_project_elysium_vr

- ↑ VirtuosityTech, "About Us". https://virtuositytech.com/index.php/about-us

- ↑ Virtual Reality Society, "Virtuality – A New Reality of Promise, Two Decades Too Soon", April 17, 2018. https://www.vrs.org.uk/dr-jonathan-walden-virtuality-new-reality-promise-two-decades-soon/

- ↑ Wikipedia, "Virtuality (product)", March 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtuality_(product)

- ↑ LinkedIn, "DigiLens founder departs…", August 5, 2020. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/digilens-founder-departs-christopher-grayson?trk=read_related_article-card_title

- ↑ Wikipedia, "Virtuality (product)", March 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtuality_(product)

- ↑ Tech Monitor, "Cybermind Scraps The Virtuality Group's Elysium", September 12, 1997. https://www.techmonitor.ai/analysis/cybermind_scraps_the_virtuality_groups_elysium_1/

- ↑ VirtuosityTech, "About Us". https://virtuositytech.com/index.php/about-us

- ↑ Wikipedia, "Virtuality (product)", March 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtuality_(product)

- ↑ LinkedIn, "DigiLens founder departs…", August 5, 2020. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/digilens-founder-departs-christopher-grayson?trk=read_related_article-card_title

- ↑ Virtual Reality Society, "Virtuality – A New Reality of Promise, Two Decades Too Soon", April 17, 2018. https://www.vrs.org.uk/dr-jonathan-walden-virtuality-new-reality-promise-two-decades-soon/

- ↑ Road to VR, "Official Virtuality '90s Game Ports Could Be Landing on Modern VR Headsets Soon", August 18, 2020. https://www.roadtovr.com/dactyl-nightmare-2-virtuality-port/

- ↑ VirtuosityTech, "About Us". https://virtuositytech.com/index.php/about-us

- ↑ Arcade History, "Dactyl Nightmare, V.R. game by Virtuality, Ltd. (1991)". https://www.arcade-history.com/?n=dactyl-nightmare&page=detail&id=12493

- ↑ Wikipedia, "Virtuality (product)", March 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtuality_(product)

- ↑ MIXED-News, "The History of Virtual Reality", August 28, 2022. https://mixed-news.com/en/the-history-of-virtual-reality/

- ↑ Wikipedia, "Virtuality (product)", March 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtuality_(product)

- ↑ Virtuality.com. https://virtuality.com/

- ↑ Kotaku, "The Man Who's Keeping 1990s Virtual Reality Machines Alive", May 27, 2016. https://kotaku.com/the-man-whos-keeping-1990s-virtual-reality-machines-ali-1778990894

- ↑ Wikipedia, "Virtuality (product)", March 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtuality_(product)

- ↑ Wikipedia, "Virtuality (product)", March 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtuality_(product)

- ↑ Electronics: The Maplin Magazine, "Virtual Reality", April 1992. https://www.worldradiohistory.com/UK/Mapelin/Maplin-Electronics-1992-04%2052.pdf

- ↑ Wikipedia, "Virtuality (product)", March 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtuality_(product)

- ↑ Wikipedia, "Zone Hunter". https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zone_Hunter

- ↑ Virtuality.com. https://virtuality.com/

- ↑ YouTube, "Boxing: game by Virtuality", May 27, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x-uE5iWJg8w

- ↑ Wikipedia, "Virtuality (product)", March 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtuality_(product)

- ↑ Virtuality.com. https://virtuality.com/

- ↑ Wikipedia, "Virtuality (product)", March 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virtuality_(product)

- ↑ Virtual Reality Society, "Virtuality – A New Reality of Promise, Two Decades Too Soon", April 17, 2018. https://www.vrs.org.uk/dr-jonathan-walden-virtuality-new-reality-promise-two-decades-soon/

- ↑ The Independent, "Dr Waldern's Dream Machines", November 28, 1993. https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/the-hunter-davies-interview-dr-walderns-dream-machines-arcade-thrills-for-spotty-youths-today-but-revolutionary-tools-for-surgeons-and-architects-tomorrow-says-the-pioneer-of-virtual-reality-1506176.html

- ↑ Virtual Reality Society, "Virtuality – A New Reality of Promise, Two Decades Too Soon", April 17, 2018. https://www.vrs.org.uk/dr-jonathan-walden-virtuality-new-reality-promise-two-decades-soon/

- ↑ Road to VR, "Official Virtuality '90s Game Ports Could Be Landing on Modern VR Headsets Soon", August 18, 2020. https://www.roadtovr.com/dactyl-nightmare-2-virtuality-port/

- ↑ Time Extension, "Virtuality Gave Us '90s VR - Now Its Legacy Is Being Celebrated In Its Home City Of Leicester", April 30, 2024. https://www.timeextension.com/features/virtuality-gave-us-90s-vr-now-its-legacy-is-being-celebrated-in-its-home-city-of-leicester