Philips Scuba

| Philips Scuba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Basic Info | |

| VR/AR | Virtual Reality |

| Type | Head-mounted display |

| Subtype | Console-Powered VR, Video headset, Vintage VR |

| Developer | Philips, Philips Consumer Electronics |

| Manufacturer | Koninklijke Philips N.V., Philips Consumer Electronics |

| Announcement Date | Late 1996 |

| Release Date | 1997-1998 |

| Price | $299 USD |

| Versions | VIV100, VIV100AT, VIV100AT01 |

| Requires | Nintendo 64, Sega Saturn, Sony PlayStation, DVD player, PC with composite video output |

| System | |

| Storage | |

| Display | |

| Display | Dual AMLCD (Active Matrix LCD), approx. 0.7 inches each |

| Resolution | 263 × 230 pixels per eye |

| Refresh Rate | 60 Hz (NTSC), 50 Hz (PAL) |

| Image | |

| Field of View | 50° diagonal (40° horizontal × 30° vertical) |

| Horizontal FoV | 40°-45° |

| Vertical FoV | 30° |

| Optics | |

| Optics | Single-element plastic lenses with fixed focus |

| Ocularity | Binocular |

| IPD Range | Fixed (no adjustment) |

| Tracking | |

| Tracking | 3 DoF Non-positional |

| Base Stations | No |

| Eye Tracking | No |

| Face Tracking | No |

| Hand Tracking | No |

| Body Tracking | No |

| Rotational Tracking | Yes (Gyroscope Based) |

| Positional Tracking | No |

| Audio | |

| Audio | Built-in stereo headphones/speakers |

| Microphone | No |

| 3.5mm Audio Jack | Yes (audio input) |

| Camera | No |

| Connectivity | |

| Connectivity | RCA composite video input, stereo audio input |

| Ports | Composite video (RCA), 3.5mm stereo audio |

| Wired Video | Yes |

| Power | External power supply via control box (9V DC) |

| Device | |

| Weight | 544 g (1.19 lb / 19.2 oz) |

| Material | Plastic with rubber face mask |

| Headstrap | Adjustable head harness with rear cradle and elastic top strap |

| Haptics | No |

| Color | Gray/Black |

| Sensors | Gyroscope |

| Input | Control box with power button, brightness/contrast controls, volume control |

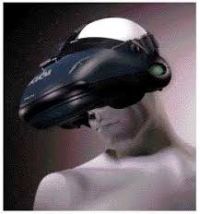

The Philips Scuba Virtual Immersion Visor (models VIV100, VIV100AT, VIV100AT01) was a head-mounted display (HMD) released by Philips Consumer Electronics in 1997-1998. Despite being marketed as a virtual reality headset during the 1990s VR craze, it was essentially a wearable television display or "video headset" that provided a stereoscopic viewing experience without true VR capabilities such as head tracking.[1][2] The device created a perceived 30-inch image at approximately 1.5 meters viewing distance.[3]

History

Development

The Scuba's technology was originally developed as a VR helmet for the Atari Jaguar home game system (released in 1993), descended from Retinal Displays' "Visor" family of HMDs. However, when that project fell through, the technology was sold to Philips, who licensed the optics and chassis design while removing the head tracking component that Atari had intended to use for its Missile Command VR game.[3][4]

Release

Philips first teased the device at trade shows in late 1996[5] and released the Scuba Virtual Immersion Visor in 1997-1998 at a retail price of $299 USD.[2][1] This price point was notably $100 more than the launch price of the Nintendo 64, making it an expensive peripheral for the time, roughly $550 adjusted for 2025 inflation.[1][5]

Market Performance

The Scuba sold approximately 55,000 units during its commercial run before being discontinued in 1999.[3] Despite Philips' marketing efforts positioning it as a virtual reality device with claims like "You hadn't played a game until you'd played it wearing an Immersion Visor," consumer reception was mixed to negative, with many criticizing its poor image quality and misleading VR branding. The molds were later reused for low-cost TV viewers in Asia, while Retinal Displays pivoted toward wave-guide optics, technology that ultimately seeded DigiLens in the mid-2000s.

Technical Specifications

Display Technology

The Scuba featured dual Active Matrix LCD (AMLCD) display panels, each approximately 0.7 inches in size, with the following specifications:

- Resolution: 263 × 230 pixels per eye[3][2]

- TV Lines: 400 TV lines[2]

- Refresh Rate: 60 Hz (NTSC) / 50 Hz (PAL)[6]

- Field of View: 50° diagonal (40° horizontal × 30° vertical effective)[2][7]

- Optics: Single-element plastic lenses with fixed focus; no IPD or diopter adjustment[5]

Physical Design

The headset weighed 544 grams (1.19 pounds / 19.2 ounces) and featured a design similar to a diving mask, hence the "Scuba" name.[2] It was heavier than contemporary video glasses such as the Sony Glasstron, which reviewers criticized for causing neck strain during extended sessions.[8] The device utilized:

- A rubber face mask that pressed against the user's face to block external light[7]

- An adjustable head harness with a rear cradle and elastic top strap for weight distribution[7]

- A rigid plastic yoke that clamped to the user's forehead[8]

- Built-in stereo headphones/speakers for audio[7]

Control Box

The Scuba included an external control box (breakout box) that housed:[7]

- Power supply input (9V DC from external AC adapter)[5]

- Headset connection port (resembling a keyboard plug)

- Volume control

- Brightness and contrast adjustment controls

- Power on/off button

- 30-minute automatic timer shut-off feature (likely to mitigate eye strain)

Connectivity

The device accepted standard-definition composite signals through:

- RCA composite video input

- 3.5mm stereo audio input (left/right channels)

- No digital inputs were offered[5]

Tracking

The device featured basic 3 degrees of freedom (3DoF) non-positional tracking using gyroscope-based sensors for rotational head movement detection.[2] However, this was limited compared to the original Atari Jaguar prototype which had included full head-tracking capabilities.

Compatibility

The Philips Scuba was promoted as universal, compatible with various gaming consoles and devices that supported NTSC or PAL composite video output:[9][10]

| Console/Device | Compatibility |

|---|---|

| Nintendo 64 | Yes |

| Sega Saturn | Yes |

| Sony PlayStation | Yes |

| DVD players | Yes |

| VCRs | Yes |

| PC with composite video output | Yes |

| Other NTSC/PAL consoles | Yes |

In practice, the low resolution limits made high-detail games appear fuzzy and text difficult to read.[1]

Reception

Critical Response

The Philips Scuba received largely negative reviews from critics and consumers. Early coverage in Ultra Game Players described it as "a TV strapped to your head," praising its novelty but criticizing image clarity and comfort.[5] Common criticisms included:

- Poor optics: Users frequently reported blurry visuals and eye strain after extended use[7]

- Misleading marketing: Despite being marketed as a VR device, it lacked true virtual reality capabilities[1]

- Limited visibility: Some users reported difficulty seeing screen corners and issues with lens placement[1]

- High price: At $299, it was considered expensive for what was essentially a head-mounted television[1]

- Physical discomfort: The 544g weight led to neck cramps and the rubber facemask left marks on users' faces[1][7]

- Health issues: Some users reported nausea, with effects compared to those of the Virtual Boy[11]

Some reviewers noted that the headset performed better when disassembled, suggesting fundamental design flaws in the optical assembly.[1] One review rated it 4/10, noting that while it outperformed competitors in field of view, its optics were subpar compared to alternatives like Virtual I/O Glasses.[7]

Legacy

The Philips Scuba has been retrospectively cited as one of the worst gaming peripherals ever made, representing the challenges and failures of 1990s attempts at consumer VR technology.[1] Today, it is valued as a collector's item among retro gaming and VR enthusiasts for its historical significance rather than its performance. Hobbyist teardown videos confirm the simple video-goggle construction and note aging capacitors as a common failure point.[6]

The device serves as an example of how marketing hype around virtual reality in the 1990s led to products that failed to deliver on their promises, and underscores the importance of comfort and functionality in modern HMD design.

Variants

Three model numbers have been identified:

- VIV100: The standard retail model[9]

- VIV100AT: A variant model[12]

- VIV100AT01: Another variant with the same specifications[13]

See Also

- Virtual Boy

- Sony Glasstron

- Olympus Eye-Trek

- Atari Jaguar VR

- 1990s in video games

- Head-mounted display

- List of virtual reality headsets

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 Retrovolve. "The Scuba Virtual Immersion Visor May Be the Worst Gaming Peripheral of All Time". July 14, 2020. https://retrovolve.com/the-scuba-virtual-immersion-visor-may-be-the-worst-gaming-peripheral-of-all-time/

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 The VR Shop. "Scuba Visor - Info, Specs, Release Date". February 19, 2022. https://www.virtual-reality-shop.co.uk/philips-scuba-visor/

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Google Arts & Culture. "Philips Scuba VR Visor head-mounted display". https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/philips-scuba-vr-visor-head-mounted-display/pAEuQPvHhOdtTQ?hl=en

- ↑ VR Society. "Virtuality – A New Reality of Promise, Two Decades Too Soon". 2018. https://vrs.org.uk

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Ultra Game Players #104. "Scuba Virtual Immersion Visor mini-review". December 1997. pp. 113-115

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 YouTube. "Philips Scuba VR headset from 1997 (VIV100) – capacitor test & teardown". February 1, 2024.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Mellott's VR Page. "The Philips Scuba Review". https://mellottsvrpage.com/index.php/the-philips-scuba-review/

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Dogey, Jonathan. "The Scuba Review". Dogey's Lair.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 ShopGoodwill.com. "Philips Magnavox Scuba Virtual Immersion Visor". https://shopgoodwill.com/Item/65691344

- ↑ Etsy. "Vintage Virtual Immersion Visor Scuba by Philips Display". https://www.etsy.com/jp/listing/1315375304/vintage-virtual-immersion-visor-scuba-by

- ↑ Reddit Gaming Post. "I still own this it was a virtual reality headset". https://www.reddit.com/r/gaming/comments/1h82oc/

- ↑ eBay. "Philips SCUBA A/V Headset VIV100AT". Item 266739527771.

- ↑ eBay. "PHILIPS MAGNAVOX SCUBA VIRTUAL IMMERSION VISOR VIV100 BOXED VINTAGE/RETRO VR". https://www.ebay.com/itm/273155691856